In a Nutshell

- PCBs are chemical compounds once widely used in the industry and found to this day in buildings and the environment.

- PCBs are considered carcinogens. They are among the twelve toxic organic substances, known as the «dirty dozen», which were banned around the world by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants signed on 22 May 2001.

- In Switzerland, PCBs had already been banned in 1972 in open systems, such as joint sealants, paints, and varnishes.

- Nevertheless, PCBs spread all over the world. They are traceable in the atmosphere, in water bodies, and in soil.

- If PCBs are found in beef, this meat is banned from sale. This happened on a farm in the Canton of the Grisons, one of Switzerland’s member states. The farmer had to have his barn decontaminated at great expense.

- At this time, neither the federal nor the cantonal governments in Switzerland are planning a comprehensive survey of PCB sources.

- Moreover, it is far from clear who should bear the costs incurred. According to current Swiss law, it is the farmer’s sole responsibility.

It will take decades before all traces of PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) have been eliminated from the environment. PCBs are industrial chemical compounds widely used around the globe from the 1930s through the 1980s. Due to their properties harmful to human beings and the environment, they were banned in Switzerland in 1986 (see box below).

But the problem was far from solved, since PCBs are persistent. They build up in the environment and enter our food chain. In addition, PCBs are often invisible, even though they are omnipresent in our environment. Every now and then, they turn up in the form of an inherited contamination.

[IMG 2]

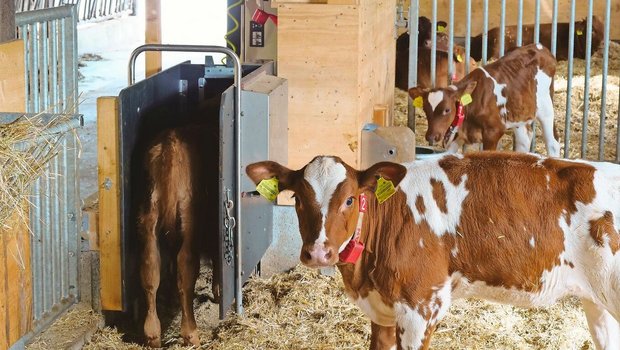

From peeling paint into cows

This was the case when PCBs turned up on a farm in a mountain village in the Canton of the Grisons, one of the Swiss Confederation’s member states. In 2018, journalist Stefanie Hablützel was the first to report on this 2013 case in Beobachter («Observer») magazine. At the time, Switzerland’s Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office (FSVO) had detected PCB quantities in veal which partially exceeded the legal limit by a factor of five. Where had the PCBs come from, and how had they found their way into the calves?

Markus Zennegg, chemist at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (Empa), explains: «Paint containing PCBs had started to peel off the barn walls. These paint flakes had been ingested by the cows and the PCBs had thus been passed on to their calves through their milk.» It was Zennegg who had discovered the PCB source in this particular barn. He is convinced that this is not the only farm where elevated quantities of PCBs could be detected – if somebody tried to find them.

Polychlorinated biphenyls

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were produced synthetically. These chlorinated chemicals once used in industry and construction are extremely stable and persistent. PCBs are electrically non-conductive, heat-resistant, and fireproof.

Due to these properties, PCBs were employed for a wide variety of uses, such as: as an insulating oil in transformers and capacitors; as an additive in anti-corrosion coating, special paints, and joint sealants. In these ways, they may have once come into a barn, where they could be released gradually, over decades, into the environment.

Deposited in fatty tissue

In contrast to PCBs from a barn wall, animals may be exposed to a diffuse PCB source on a pasture, since PCBs can also be found in soil. These deposits may hail from a time when exhaust air from incinerators was not filtered as thoroughly as it is today. PCBs spread through the air across the entire planet. They entered the soil via precipitation, and cows absorb them when ingesting small soil particles. Inside the animals, PCBs are deposited in fatty tissue. Additionally, mother cows pass them on to their calves through their milk.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies PCBs as carcinogenic for humans.

Banned since 1986

In Switzerland, PCBs were banned in all open uses (paints, varnishes, anticorrosive coating, etc.) in 1972. In 1986, polychlorinated biphenyls were finally banned entirely.

There is no official PCB inventory

The PCB content of animal products is measured as part of the FSVO’s national impurity test program. According to their report, they found that PCB content in all samples taken in 2020 (18 beef, 52 pork, 15 milk, 20 egg, plus other samples) was below the critical threshold and thus in compliance.

[IMG 3]

Does that mean that PCBs are history? Or do these toxic substances just remain undetected, until paint starts to peel again at some place? Nobody seems to know for sure. According to the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN), there is no official PCB inventory in Switzerland, apart from electrical systems containing PCBs (transformers and large capacitors). The office also reports that there is no comprehensive monitoring.

Only in the Rhine River, in Lake Geneva, and in the lakes of the Canton of Ticino in Southeastern Switzerland, PCB concentrations in suspended matters and in fish are being measured regularly. There is a good reason for monitoring the Rhine: Europe’s tenth-longest river supplies thirty million people in Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands with drinking water.

Although in lower quantities, PCBs are still present in the environment

In order to get an idea of the presence of PCBs, in spite of patchy monitoring, FOEN commissioned the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich to model PCB material flows in Switzerland, based on all available information about PCB import, use, and emissions.

According to these estimates, the peak level of 4,000 metric tons of PCBs in circulation had been reached in 1975. Today, 217 tons are still in use, including 86 tons in anticorrosive paint and 86 tons in joint sealants. Additionally, 300 tons of PCBs have been deposited in waste landfills and 42 tons in the soil.

Although the presence of PCBs has been significantly reduced since their peak in 1975, PCBs have not disappeared completely in Switzerland.

Pilot project for PCB survey is currently on hold

However, there is no systematic monitoring on Swiss farms and in Swiss barns to this day, as our research with the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN), the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office (FSVO), and the Federal Office for Agriculture (FOAG) has shown.

Once, a pilot project in the Canton of the Grisons had been developed, in order to gather information on PCB sources on farms, but this project is currently on hold. According to the federal agencies, the cantons are in charge of implementing these measures.

Daniel Buschauer from the Grisons Office of Agriculture and Geoinfomation says: «The need to take action has been realized across Switzerland, and we discussed the implementation of a pilot project in our canton, but we came to the conclusion that we are unable to implement it at this time, as there is too much uncertainty.»

The big question: How will we proceed if we find PCB?

Buschauer mentions the lack of methodology, the enormous expense, and the difficulties in locating the sources. Further challenges include barn selection and sampling methods. In addition, there is the cost of decontamination, which can quickly add up to significant amounts. These are reasons for not taking samples in the first place.

[IMG 4]

«We simply don’t know how to handle this, if PCBs are found. Available investment subsidies from both the federal and cantonal governments notwithstanding, an affected farm may very well face bankruptcy,» Buschauer explains. He expects the federal government to prescribe clearly defined, uniform procedures for the entire country, and to support the cantons in their implementation.

Fixing PCB-contaminated barn walls is expensive

Whenever beef or veal is as severely contaminated as on the Grisons farm, its sale is prohibited: a major loss for the farmer – on top of the cost of decontaminating the barn.

The barn in the Grisons was completely wrapped, before the paint was removed with special tools, in order to avoid particulate emissions. The work was performed at subatmospheric pressure to prevent the release of PCB-contaminated particles into the environment. According to Daniel Buschauer, the total cost amounted to 270,000 Swiss francs, including the loss of livestock and personal contributions. About one quarter of the money went into sampling, environmental analysis, and the decontamination concept.

This is quite a sum of money for a single small barn in a mountain village. Thanks to financial support from the Canton of the Grisons, the farm managed to survive. But who will pay if more contaminated farms turn up?

Farmers are responsible for uncontaminated meat

According to current law, owners are responsible for financing barn decontamination. That is the gist of a 38-page report in which federal authorities, together with cantonal veterinarians and chemists, discuss how to handle PCBs. In addition, the canton may offer financial support. [IMG 5]

A farmer who falls on hard times as a result of contamination may thus apply for an interest-free loan, which would enable him to rebuild the barn. However, there is no provision at this time for indemnifying him for the removal and disposal of PCB-contaminated material or the loss of livestock. And, of course, he has to repay the loan eventually.

On the matter of financing, the FOAG writes: «There is currently no option for the federal government to provide financial aid in cases of PCB contamination. The FOAG is looking into other cost-sharing options.» At the same time, the office emphasizes that it is the farmers’ own responsibility and in their own best interest to produce safe food. Furthermore: «Investigation is important in cases of suspected contamination.»

Simple measurements in barns

In order to determine a risk in the first place, farmers are being informed in a new pamphlet published by the Swiss Association for the Development of Agriculture and Rural Areas (AGRIDEA). Moreover, various educational courses were offered in 2021 to create awareness for the presence of PCBs on farms.

[IMG 6]

Markus Zennegg advocates more comprehensive action, such as monitoring in barns: «There are measuring devices that scan the chlorine content of a certain substance on the surface. This would be a simple way for an initial measurement.» The chemist suggests training consultants who visit the farms anyway in how to conduct PCB risk assessments. In addition, the search could be narrowed down: Joint sealants and paints applied after 1975, as well as capacitors manufactured more recently than 1986, would, in all likelihood, be PCB-free.

Zennegg estimates that initial measurements and assessments could be conducted without spending large sums of money. These would only be needed if PCB sources were actually detected – but the fear of this happening seems to block an organized approach on the part of public authorities. Beobachter magazine already recognized this in 2018, and very little has changed since.

Very small amounts – but not to be neglected

PCBs are thus present in many places throughout the environment, yet they only turn up now and then, and even less frequently do they enter the public mind. It sounds menacing and has all the makings of a latent threat to public health. This is borne out by facts and figures: Every week, each Swiss citizen absorbs twelve picograms of PCB per kilogram of body mass – this is clearly above the level of two picograms, which the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) considers safe.

But that is no reason to get worried, says Markus Zennegg: «These tolerable exposure levels are set extremely low and include a wide safety margin.» Just imagine: one trillion picograms – a one with twelve zeroes – add up to a single gram. This is a very low threshold, which is easily exceeded. The cows on the Grisons farm, for example, did not show any signs of ill health.

And yet, Markus Zennegg emphasizes: «We must not forget the PCBs but have to tackle the problem head-on.» Contamination has to brought out into the open.

Suggested PCB safeguard measures for farms

What can I, as a farmer, do to keep PCBs out of animal products?

Preventive:

- Avoid feeding soiled fodder in the field and in the barn, in order to minimize the intake of soil particles.

- Do not let animals drink from running or open waters, in order to minimize the intake of stream sediments.

In case of a critical PCB concentration:

- Slaughter fattenable weaners at an older age, since increased body mass has a diluting effect: The volume of PCBs per unit of body mass decreases.

- Wean calves when at a younger age, in order to reduce the amount of PCBs absorbed via milk from their mothers.

- Feed corn silage, in order to reduce the animals’ PCB intake.

- Let the herd graze in other places during the summer.

These and other suggestions can be found in the pamphlet entitled «PCBs in Animal Husbandry: Causes and Remedies» available in German, French, and Italian, published by the Swiss Association for the Development of Agriculture and Rural Areas (AGRIDEA).